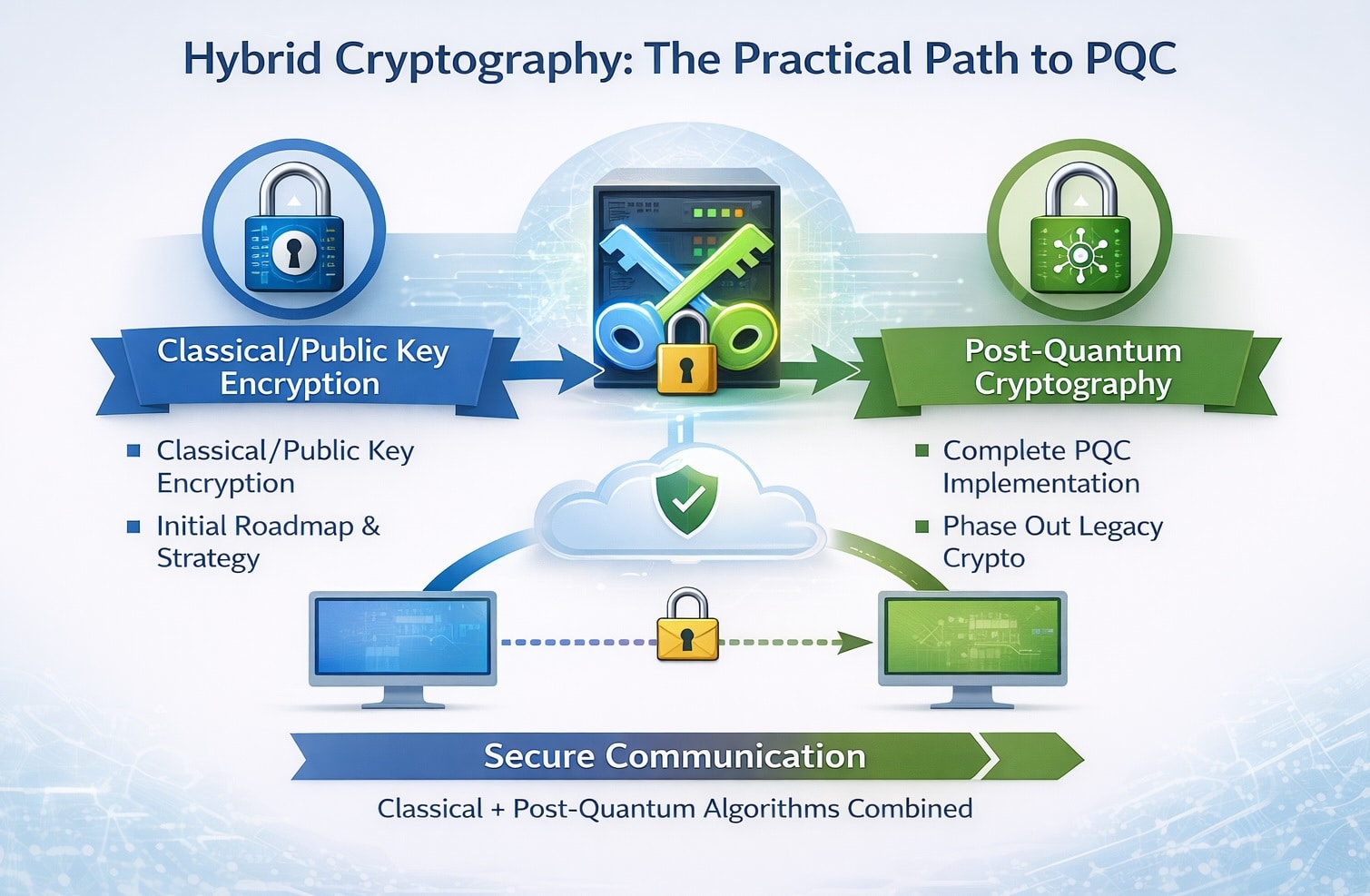

Hybrid cryptography combines classical public-key algorithms (like RSA/ECC) with new post-quantum algorithms in the same operation. In simple terms, a hybrid scheme requires an attacker to break both a traditional algorithm and a quantum-safe algorithm to compromise a secret. For example, a TLS 1.3 handshake can mix an elliptic-curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH) key exchange with a post-quantum KEM (such as CRYSTALS-Kyber), deriving a shared secret from both. Likewise, a digital certificate or update might carry both an ECDSA signature and a PQC signature (e.g. Dilithium). As long as at least one of the two algorithms remains secure, the data stays protected. In practice, legacy systems simply ignore the unfamiliar PQC parts (often placed in non-critical certificate extensions), while updated clients verify both signatures. Thus hybrid cryptography lets old and new systems interoperate smoothly during the transition.

"Hybrid cryptography pairs classical and post-quantum algorithms to protect against future quantum threats."

PQC Lab

Evaluate & explore ML-DSA–based certificate issuance, signing and verification in a non-production environment.

Why Hybrid is Needed

We’re in a paradoxical moment: quantum computers threaten today’s ciphers, but fully replacing them is risky. Public-key systems like RSA and ECC can be broken by future quantum computers, and adversaries can already record encrypted traffic now for a “harvest-now, decrypt-later” attack.

On the other hand, NIST’s new PQC algorithms (like Kyber and Dilithium) are standardized but they are still new and may uncover unexpected weaknesses. Jumping immediately to pure PQC could break legacy devices or fail in practice.

Hybrid cryptography resolves this by overlapping the two worlds: even if one algorithm fails (classical or quantum-safe), the other still protects the data.

Experts view hybrid as a prudent interim solution.

- The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) doesn’t expliticitly recommends hybrids rather suggest to move to pure PQC algorithms.

- The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) advises that any hybrid scheme should be only an interim step toward full PQC.

- European bodies like ENISA and the EU’s PQC Roadmap likewise promote hybrid deployment to integrate PQC without disruption.

In short, hybrid schemes “buy time and assurance” you get quantum-safe protection against future attacks today, without fully abandoning known-good classical algorithms.

Hybrid in TLS and Secure Channels

TLS/HTTPS

Modern web security (TLS 1.3 and HTTP/3/QUIC) is on the front lines of PQC transition. In hybrid TLS handshakes, the client and server perform both a classical Diffie–Hellman exchange and a post-quantum key encapsulation in parallel. The final secret is derived from both parts. This approach has been field-tested: Google’s Chrome and Cloudflare enabled hybrid X25519+Kyber for a subset of users, and by early 2024 about 1.8% of TLS 1.3 connections to Cloudflare used post-quantum cryptography. (Cloudflare expects usage to grow to double digits as browsers like Chrome and Firefox broaden support.)

The shift has been smooth: adding a lattice-based KEM like Kyber to ECDH typically costs only 1–2 ms more latency and ~1–2 KB extra data in the handshake. Modern networks can easily absorb this, and clever tuning (e.g. larger TCP windows) can hide the overhead. Importantly, hybrid TLS falls back gracefully: if a client doesn’t understand the PQ part, it ignores it and completes a purely classical handshake, so connectivity is never broken.

The IETF is formalizing these techniques (see drafts for hybrid ECDH+Kyber in TLS 1.3). In summary, hybrid TLS has reached real-world pilots in major browsers and CDNs, moving quickly from experiment toward mainstream.

OpenSSH has supported post‑quantum hybrid key exchange since OpenSSH 9.0 (released April 2022), where the hybrid algorithm sntrup761x25519‑sha512@openssh.com – combining the Streamlined NTRU Prime post‑quantum scheme with the classical X25519 ECDH key exchange – was made the default key exchange method for SSH connections.

This hybrid approach ensures that key material is derived from both a classical and a post‑quantum component, mitigating “store now, decrypt later” threats where encrypted sessions captured today could be decrypted in the future once quantum computers become capable.

Other protocols

- QUIC (HTTP/3) uses TLS 1.3 handshakes, so it inherits the same hybrid capabilities. Work is also underway to embed hybrid key exchange into VPN/IPsec. For instance, IETF RFC 9370 (2023) extended IKEv2 to allow multiple key exchanges, explicitly enabling a hybrid DH+Kyber setup.

- Messaging protocols (like Signal’s MLS) and future secure layers (Encrypted Client Hello, secure WebSockets) can similarly use hybrid HPKE modes by combining X25519 with Kyber. In practice, any system that already does public-key key exchange can add a PQC key in parallel to become “quantum-safe ahead of time.”

Hybrid in PKI and Certificates

Transitioning public-key infrastructures (PKI) is one of the trickiest parts of PQC migration. A common hybrid approach is to issue composite X.509 certificates containing both a classical and a post-quantum key.

In a hybrid certificate, the CA embeds two public keys and signs each: one key uses a traditional algorithm (e.g. RSA or ECDSA) with a matching classical signature and the other uses a PQC algorithm (like Dilithium) with a PQ signature.

An example: a web server certificate might contain an RSA key signed by the CA’s RSA key and also a Dilithium key signed by the CA’s Dilithium key, both for the same identity. Browsers or clients that support PQC will validate the Dilithium signature while legacy clients simply ignore the PQC fields (these are placed in non-critical extensions) and validate the RSA signature as usual. This guarantees backward compatibility: there’s no “big switch-over day,” and certificates work for old and new systems simultaneously.

Hybrid certificates do come with a cost

Every certificate chain becomes larger (often tens of kilobytes instead of a few), which can slightly slow handshakes or require tuning servers to accept larger certs. In practice this has been deemed an acceptable price for continuity during migration.

Standards groups and CAs are actively working on profiles for hybrid certificates, and some proof-of-concept implementations already exist.

“Hybrid and composite approaches may provide short-term value, but they’re not the destination”, since ultimately all systems will need to adopt pure PQC. In other words, once PQC is fully trusted by the ecosystem, organizations will phase out the classical keys and signatures.

Hybrid for Digital Signatures

The same idea applies to digital signatures on code, documents and firmware. To protect long-lived signatures, a common hybrid pattern is dual signing: sign the artifact twice, once with a classical algorithm and once with a PQC algorithm. For example, a software update package might carry both an ECDSA signature and a Dilithium or LMS (hash-based) signature. Legacy verifiers will check the ECDSA signature as before while updated software can verify the PQC signature. This “two keys, two signatures” model mirrors hybrid certificates. It thwarts a quantum adversary because forging the update requires breaking both signature schemes.

The same applies to document signing formats (PDF/PKCS7, XML, etc.): new standards are emerging to allow multiple concurrent signature formats. Note that unlike encryption, signature forging can’t be postponed by storing ciphertext; but still, dual-signing ensures that if one scheme is compromised in the future existing signed artifacts aren’t automatically invalidated.

Benefits and Trade-offs of Hybrid Approaches

Hybrid cryptography offers clear benefits in a PQC transition:

- Defense-in-depth: By requiring an adversary to break both a classical and a PQC algorithm, hybrid schemes are strictly stronger (or at least no weaker) than either alone. This “belt-and-suspenders” setup hedges against the risk that a new PQC scheme might be broken or have hidden flaws.

- Compatibility: Hybrids let organizations retain existing systems and protocols without disruption. Old clients/servers can ignore the PQC portions, so infrastructure keeps working while PQ readiness grows.

- Incremental deployment: You can roll out PQC support in stages. For example, start by upgrading servers to hybrid TLS while waiting for client updates, or pilot PQC in internal services only. This avoids the “big bang” risk of switching to pure PQC all at once.

- Futureproofing “now”: Hybrid schemes protect today’s data against future capture. Even if an adversary records encrypted traffic now, they’d still need to break a quantum-safe component (like Kyber) later

- Expert-backed approach: Leading authorities encourage hybrids during the transition. For instance, the NSA explicitly endorses hybrids “as needed” when pure PQC isn’t yet practical, and bodies like NIST, ENISA and the EU roadmap highlight hybrids as a way to migrate without breaking everything.

However, hybrids involve trade-offs:

- Performance and size overhead:

-

Running classical and post-quantum algorithms in parallel inevitably increases computational and message overhead. In practice, hybrid TLS and SSH handshakes introduce only a small additional latency, typically on the order of a few milliseconds or less on modern systems, and require additional handshake data, with lattice-based KEMs such as Kyber adding a few kilobytes to key-exchange messages.

-

Similarly, hybrid or post-quantum certificates and signatures are significantly larger than their RSA or ECDSA counterparts. While lattice-based signatures moderately increase certificate size, hash-based schemes such as SPHINCS+ can produce signatures tens of kilobytes in size, making them unsuitable for many interactive protocols today.

-

These size increases can expose limitations in legacy middleware and network devices. Early large-scale experiments with hybrid TLS reported cases where oversized ClientHello messages were dropped by older routers, firewalls, or TLS inspection devices, requiring careful interoperability testing and, in some cases, protocol or deployment tuning before broad rollout.

-

- Complexity:

- Hybrid solutions mean managing two sets of algorithms, key sizes, and parameter sets. Systems must be “crypto-agile” to handle new key types, and hardware (like HSMs or IoT chips) may need firmware updates for PQC support. Mixing two signature and key formats can complicate protocol code and certificate handling.

- No panacea: Ultimately, hybrid is an intermediate stage. Hybrid or composite schemes are “temporary tools for migration, not permanent solutions”. Every system will eventually need a one-time breaking change to fully move to PQC. Organizations must plan to transition the classical parts away once PQC is fully vetted and ubiquitous.

Where Hybrid Cryptography Is Used Today

Hybrid schemes are already seeing real-world use in several areas:

- TLS/HTTPS: As noted above, Internet giants are testing hybrid TLS. Cloudflare reported ~1.8% of HTTPS connections using post-quantum key exchange by early 2024 (thanks to Chrome’s experiment) and this is growing as more clients update. Firefox Nightly builds include hybrid TLS support, and Apple has added PQC to iMessage as of 2024. Popular end-to-end protocols (Signal) have integrated PQ for messaging. In summary, hybrid TLS has moved from academic idea to large-scale trials at major vendors.

- SSH: OpenSSH 9.0 (April 2022) made a hybrid KEX (Curve25519+NTRU Prime) the default. This preemptively thwarts the “record now, decrypt later” threat for SSH connections. The rollout was smooth: servers and clients fell back to old key exchange only if necessary, and performance impact was negligible. Today virtually all updated OpenSSH deployments are “hybrid by default” for key exchange.

- VPN/IPsec: Organizations rely on IPsec for site-to-site and remote VPNs. The IETF has standardized ways to add PQ exchanges into IKEv2: RFC 9370 (2023) explicitly permits multiple Diffie–Hellman steps, allowing a PQC KEM to be run alongside the classical DH. Drafts are testing ECDH+Kyber combos using new intermediate messages for large keys. In practice, some agencies and vendors are beginning hybrid VPN pilot projects (for example, a government VPN may run both X25519 and Kyber to derive its session key).

- PKI and Certificates: Government and enterprise PKIs are starting to explore hybrid issuance. IETF and CA/Browser Forum working groups have drafts for hybrid certificate profiles. Certain government Certificate Authorities are internally testing dual-key certs right now. Early use cases include controlled systems like mutual-auth VPNs or secure email, where both sides can be upgraded in sync. (The U.S. GSA’s “Shatterproof Digital Identity” project, for instance, requires TLS servers to support classical, PQ, and hybrid certs)

- Software/Firmware Signing: High-assurance code and firmware updates are critical areas. Many organizations will deliver updates with both an old and a new signature.

- Pilots and Early Adoption: Across industries, PQC pilots often use hybrid encryption as the first step. For example, financial institutions’ PQC roadmaps suggest piloting hybrid schemes on internal VPNs or inter-datacenter links. An enterprise may spin up a dual-key internal CA for code-signing or document-signing tests. Similar pilots are underway in government networks, telecoms, and critical infrastructure: any system with long-lived encrypted data or keys is a candidate for hybrid protection.

- Standards and Regulations: While not deployments per se global standards and regulations reflect hybrid use. The EU’s “Post-Quantum Roadmap” encourages PQC alongside legacy crypto. The UK NCSC’s upcoming guidance warns that hybrids must remain temporary, implicitly endorsing that they will be used in the near term. In short, hybrid crypto is featured in many corporate and government PQC strategies right now.

FAQ

Why is adopting Post-Quantum Cryptography more than just replacing algorithms?

Post-Quantum Cryptography impacts the entire cryptographic lifecycle, not just algorithms. PQC introduces significantly larger keys and signatures, which affect certificate sizes, TLS handshakes, storage, logging, HSMs, firmware, and network performance. Existing PKI systems, protocols, and applications were optimized for RSA and ECC and often assume small key sizes and fast operations. Migrating to PQC therefore requires architectural changes, crypto-agile designs, and extensive testing across infrastructure, applications, and third-party dependencies.

What are the biggest technical challenges with PQC algorithms today?

The main technical challenges include larger key and signature sizes, increased computational overhead, and ecosystem immaturity. PQC algorithms such as ML-KEM and ML-DSA increase bandwidth usage and memory requirements, which can strain constrained environments like IoT, smart cards, and embedded systems. In addition, many protocols and hardware platforms are still adapting to support PQC efficiently, and some cryptographic libraries and devices are not yet fully optimized or certified.

Why is hybrid cryptography considered necessary during the PQC transition?

Hybrid cryptography is necessary because PQC algorithms are still new and classical algorithms remain trusted today. A hybrid approach combines classical and post-quantum algorithms so that security holds even if one algorithm is later weakened. This approach ensures backward compatibility, reduces migration risk, and aligns with guidance from NIST, NSA, and ENISA. Hybrid deployments allow organizations to transition gradually while maintaining interoperability and compliance during the multi-year migration period.

How do legacy systems and vendors slow down PQC adoption?

Many legacy systems have cryptography hard-coded into firmware, protocols, or application logic, making algorithm replacement difficult or impossible without major upgrades. Additionally, organizations depend on vendors, cloud providers, and hardware manufacturers for PQC support. If vendors are not PQC-ready, enterprises cannot migrate critical systems independently. This creates a dependency-driven timeline, where PQC adoption must align with vendor roadmaps, software updates, and hardware refresh cycles.