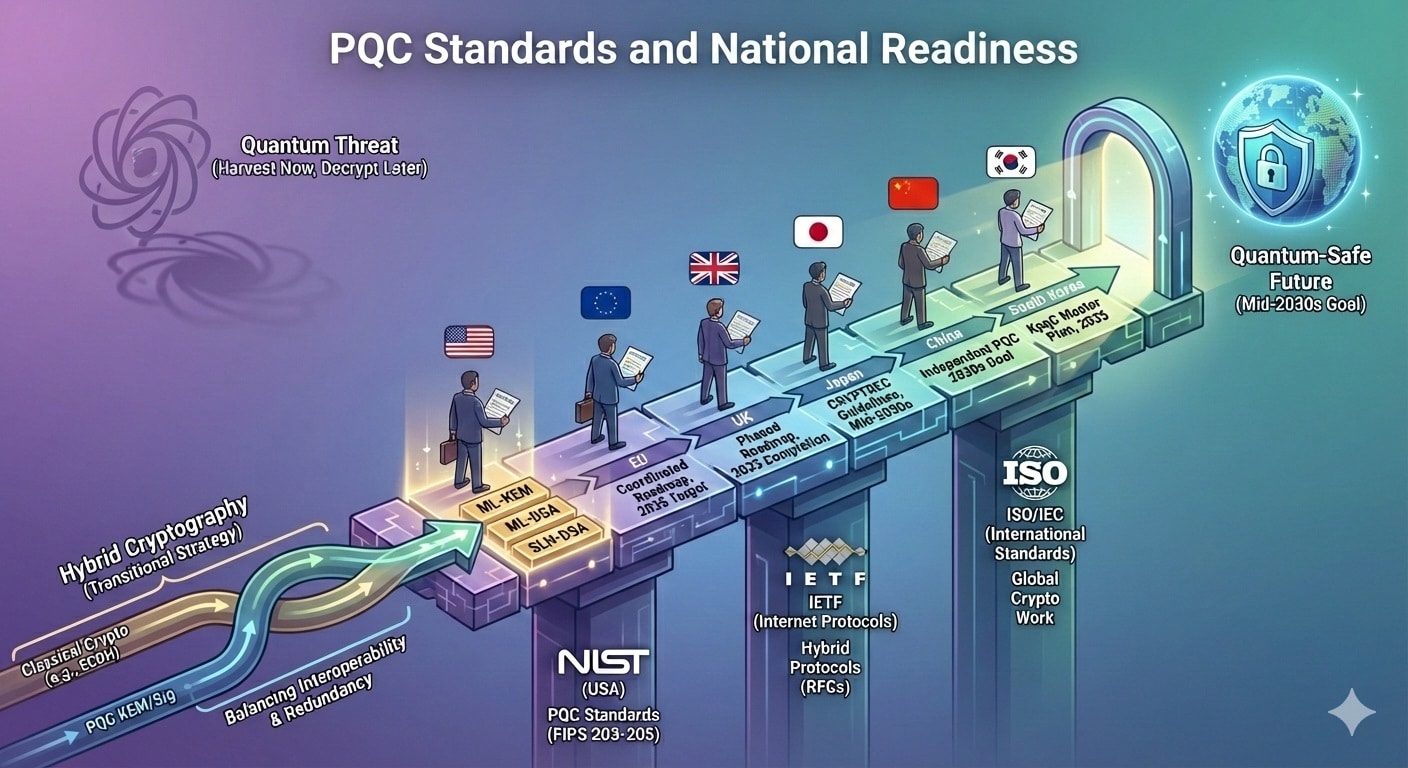

Leading standards bodies and governments worldwide are actively preparing for the post-quantum era.

- NIST has finalized its first PQC standards (FIPS 203–205) in 2024 and continues to evaluate backups [1].

- IETF is defining terminology and protocol extensions (e.g. hybrid key exchange drafts, RFC 9370, RFC 8784) to support PQC in Internet protocols [2][3].

- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC27 (the global IT security committee) is also organizing work on quantum-safe cryptography (e.g. new parts for stateful hash signatures and a “Quantum Technologies” joint working group).

In short, worldwide standards efforts are converging on a small set of algorithms (lattice-based KEM/signatures, hash-based signatures) that underlie formal PQC standards [1]. At the same time, national cybersecurity agencies are issuing roadmaps and guidance:

- U.S. NSA’s CNSA 2.0 profile mandates PQC in National Security Systems by 2035 [4]

- EU and UK have published timelines targeting wide PQC deployment by the mid-2030s [5][6].

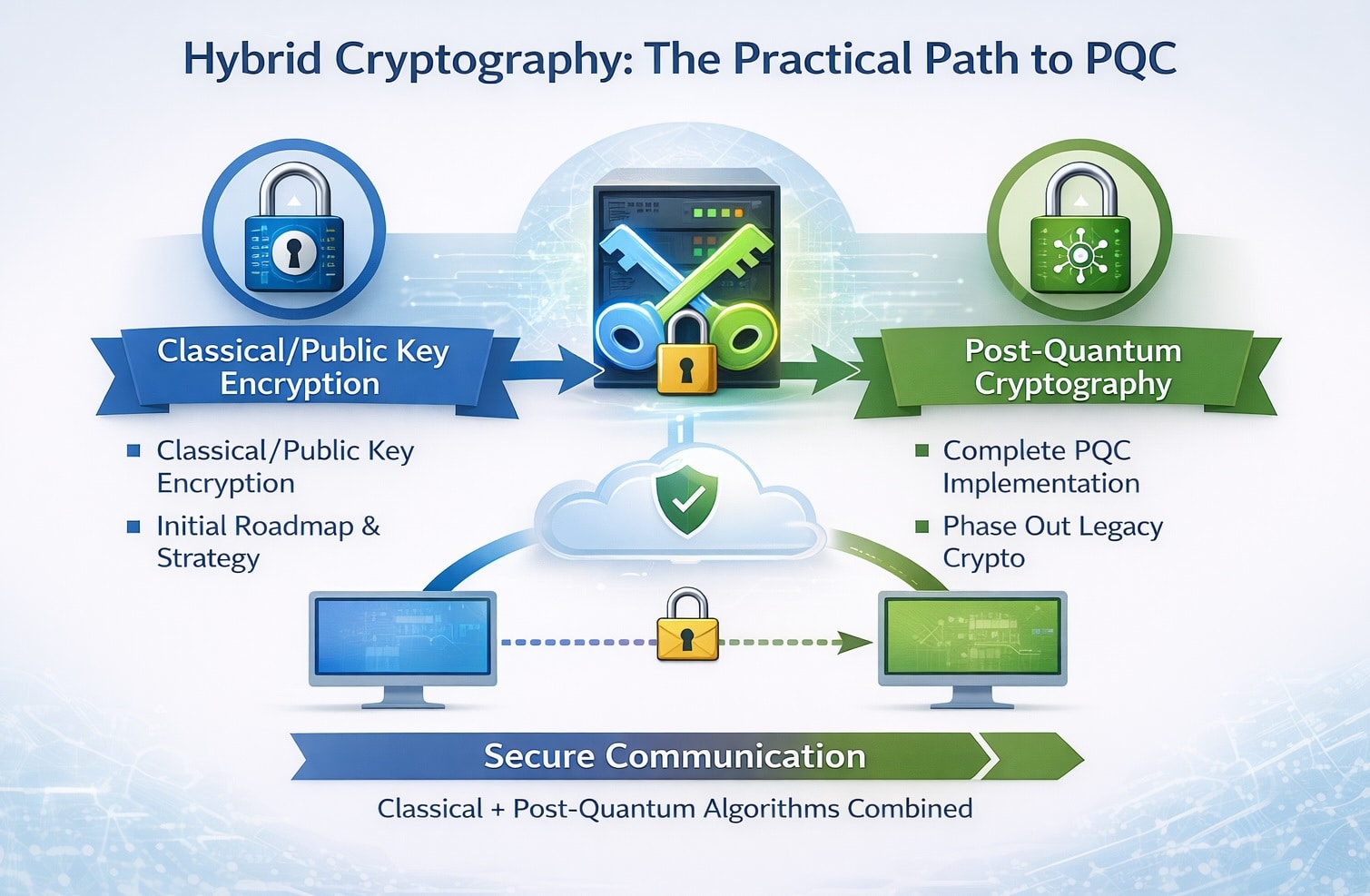

Governments recognize that hybrid schemes (combining classical and quantum-safe algorithms) will be an important transition strategy [2][7], balancing interoperability and redundancy.

PQC Lab

Evaluate & explore ML-DSA–based certificate issuance, signing and verification in a non-production environment.

Formal PQC Standardization Efforts

-

NIST (USA):

-

NIST’s PQC project (initiated 2016) selected four families of algorithms.

-

In Aug 2024 NIST published FIPS 203–205 as the first formal PQC standards: ML-KEM (based on Kyber) for encryption (FIPS 203), ML-DSA (Dilithium) for signatures (FIPS 204), and SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+) as a stateless hash-based backup (FIPS 205)[1]. (A FIPS 206 for Falcon was drafted in 2024.) These documents include implementation details, key sizes, etc., and NIST is urging organizations to start integrating them immediately[1][8].

-

NIST is also continuing evaluation of “backup” schemes (e.g. HQC, Classic McEliece) for future standards. NIST’s related SP 800-series and IR publications (e.g. SP 800-208 on hash-based signatures) and a new SP 800-241 (PQC benchmarking) support adoption and validation.

-

-

IETF (Internet protocols):

-

The IETF is addressing PQC threats by extending protocols to support hybrid and post-quantum algorithms. Notably, RFC 9794 (Sept 2022) establishes terminology for “PQ/T hybrid” schemes.

-

The IETF TLS Working Group is developing an informational draft for hybrid key exchange (TLS 1.3)[2]. That draft defines hybrid key exchange as using multiple KEX algorithms in parallel so that security holds if at least one remains unbroken[2]. In practice this means negotiating and mixing a classical algorithm (e.g. X25519) with a PQ KEM (e.g. ML-KEM) in the TLS handshake.

-

For IKEv2 (VPN key exchange), IETF published RFC 8784 (June 2020) to mix preshared keys for post-quantum resistance[3], and RFC 9370 (May 2023) to allow multiple simultaneous key exchanges.

-

RFC 9370 explicitly notes that “if any part of the component key exchange is post-quantum, the final shared secret is post-quantum secure”[7]. These extensions do not yet mandate specific PQC algorithms, but they provide the framework for transitioning existing protocols.

-

-

ISO/IEC (International Standards):

-

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 27 (the information security technical committee) has begun formal work on PQC. For example, ISO/IEC 14888-4:2024 now includes stateful hash-based signature mechanisms (XMSS/LMS) to address long-term security[1].

-

A Joint Working Group (JWG 7) on “Quantum Technologies” has been formed to recommend actions on quantum-safe cryptography across ISO/IEC. (As an example of ISO’s view on the threat, their SC 27 Journal noted that quantum computers will “eventually render the security of all widely implemented public-key cryptographic schemes ineffective”[9].)

-

Detailed ISO/IEC encryption or signature standards for NIST’s new algorithms are not yet published, but it is expected that ISO/IEC will adopt or mirror many of them once ratified, as it has done historically with algorithms like AES, RSA, ECDSA, etc.

-

National Readiness and Guidance

-

United States (NSA/CNSA, NIST, CISA): The U.S. has set one of the most explicit roadmaps.

-

In September 2022 the NSA announced the Commercial National Security Algorithm (CNSA) 2.0 suite, which includes CRYSTALS-Kyber (ML-KEM) and CRYSTALS-Dilithium (ML-DSA) for all protection levels. Crucially, NSA expects migration of all National Security Systems to PQC by 2035[4] (in line with NSM‑10 directives).

-

In practice this means agencies and vendors must adopt the new standards (at “security level V”) before that deadline. NIST’s FIPS documents (203–205) implement this suite and are meant for government and industry use; NIST also plans official recommendations (SP 800-227) by 2025–26.

-

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Commerce and CISA are beginning to inventory critical systems. (Note: NSA/CNSA allows hybrid key establishment using PQC plus ECC, but for now discourages hybrid signatures in CNSA‑protected contexts.) These timelines are hard mandates for classified and other “NSS” systems; the rest of government and industry tend to follow NIST guidance.

-

-

European Union (ENISA, Commission, ETSI):

-

The EU’s strategy stresses coordination and consistency. In April 2024 the European Commission issued a “Coordinated Implementation Roadmap” recommending Member States begin PQC transitions in lockstep[10].

-

A technical NIS Cooperation Group report (June 2025) elaborates milestones: countries should initiate planning by 2026, replace critical and high-risk cryptosystems (e.g. devices with long-lived keys) by ~2030, and complete PQC migration of all feasible systems by 2035[6]. ENISA and ETSI have also published studies and guidelines.

-

Notably, ENISA’s Post-Quantum Integration Study (2022) encouraged enterprises to plan for hybrid TLS and future PQC certificates. EU agencies generally recommend hybridization now as a pragmatic step, and plan formal mandates on PQC once standards are stable. Overall, the EU timeline mirrors the U.S.: prepare now, early deployment by early 2030s, full PQC adoption by mid-2030s.

-

-

United Kingdom (NCSC):

-

The UK NCSC has issued detailed migration guidance.

-

In March 2025 NCSC released a phased roadmap for critical sectors: prepare and plan (up to 2028), implement high-priority migrations (2028–2031), and complete PQC adoption by 2035[5].

-

NCSC emphasizes that affected organizations should inventory crypto now, prioritize long-lived data, and coordinate with international partners. (NCSC explicitly supports hybrid use as an interim measure.)

-

UK policy aligns with U.S./EU targets: PQC in government and key industries by 2035.

-

The NCSC also highlights specific technical challenges (e.g. PQC in TLS/WebPKI, IoT devices) and encourages early involvement in standards.

-

-

Japan:

-

Japan’s cryptographic authority (CRYPTREC) and the Cabinet’s cybersecurity bodies are actively planning PQC migration.

-

CRYPTREC publishes annual “Cryptographic Technology Guidelines”; the 2024 Edition (PQC) and associated reports guide Japanese agencies.

-

In 2023 CRYPTREC released PQC transition guidelines that endorse NIST’s choices (Kyber, Dilithium, etc.) while stipulating use of national symmetric primitives (e.g. Camellia) where applicable[11].

-

The National Center of Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity (NISC) is coordinating a national effort (per its 2025 cybersecurity strategy) and running pilot programs to evaluate PQC implementations.

-

While Japan has not publicly set a single deadline, its posture is consistent with global practice (aiming for wide PQC use by the mid-2030s) and emphasizes cryptographic agility across government systems.

-

-

China:

-

China is pursuing an independent PQC approach.

-

In early 2025 the Chinese Cryptography Standardization Technical Committee (ICCS) issued a global call for new PQC algorithms (public-key, hash, block ciphers)[12][13].

-

This reflects China’s intent to develop “homegrown” algorithms alongside monitoring NIST. Indeed, Chinese teams submitted several candidates (e.g. LAC KEM, Aigis signature) to the NIST process and have run internal contests since ~2018.

-

The new ICCS initiative will evaluate both domestic and international proposals; it suggests that China will eventually have its own PQC standards (likely making them mandatory in government/commercial use).

-

Official Chinese timelines are not public, but the urgency is evident: planning PQC-standard publications by mid-2020s and implementation in critical systems soon after.

-

-

South Korea:

-

South Korea has a defined PQC program under its National Intelligence Service (NIS).

-

From 2021–2024 Korea ran the KpqC competition, selecting four final PQC algorithms (a variant of Dilithium, a lattice KEM like Kyber, etc.)[14]. These form the basis of Korea’s PQC Master Plan (published 2023).

-

Korea’s roadmap targets full PQC deployment by 2035 – in line with US/EU/UK[15]. The next phase (from 2026) will focus on procedure and system support for cryptographic migration.

-

The Korean Agency for Defense Development and KISA (Korea Internet & Security Agency) are also testing PQC in TLS and VPN pilots. Overall, Korea is moving swiftly: its NIS strategy notes that being on schedule for a 2035 transition “aligns with European and US timescales”[15].

-

Other countries like Canada, Australia, and Singapore have issued PQC strategies or guidance aligning with the US/EU timeline.

- Canada’s Communications Security Establishment (CSE) is updating its guidance

- Australia’s ASD calls for phasing out classical public-key crypto by ~2030

- Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency recommends hybrid/TLS planning; etc.)

FAQ

Why are governments prioritizing Post-Quantum Cryptography at a national level?

Quantum computing poses a systemic risk to national digital trust, impacting government PKI, citizen identity systems, defense communications, and critical infrastructure. Unlike typical cyber threats, quantum attacks can retroactively break encrypted data via Harvest-Now-Decrypt-Later strategies. National PQC programs ensure long-term confidentiality, legal validity of digital signatures, and sovereignty over cryptographic standards

Which global standards bodies are defining Post-Quantum Cryptography?

PQC is being standardized through coordinated efforts by:

-

NIST (USA) – PQC algorithm standardization (e.g., ML-KEM, ML-DSA, SLH-DSA)

-

ETSI (EU) – Migration guidance, hybrid cryptography, and telecom readiness

-

ISO/IEC – International cryptographic standards for global interoperability

-

IETF – Protocol updates for TLS, IPsec, and secure communications

Together, these bodies ensure PQC adoption is interoperable, auditable, and legally defensible.

How are nations translating PQC standards into national readiness programs?

Leading nations are implementing multi-phase PQC roadmaps, including:

-

Cryptographic asset inventories across government systems

-

Mandatory crypto-agility requirements for vendors

-

Hybrid cryptography deployments in national PKI

-

Sector-specific timelines for defense, finance, energy, and telecom

These programs recognize PQC as a long-term infrastructure upgrade, not a point solution.

What does national PQC readiness mean for enterprises and infrastructure providers?

National PQC strategies directly influence regulatory expectations and procurement rules. Enterprises supporting government, financial, or critical services will increasingly be required to:

-

Support NIST-approved PQC algorithms

-

Demonstrate crypto-agility and hybrid readiness

-

Align with national and regional migration timelines

Organizations that prepare early reduce compliance risk and gain strategic advantage as mandates emerge.